WHEN the SS Truro arrived off Durban on November 16, 1860, bringing the first group of indentured labourers, the first newspaper to record the event appears to have been the Natal Star, a weekly, which ran a brief report on November 17, noting that “the Truro anchored about five o’clock last evening and she is said to have on board 250 Coolies”. A word that was the currency of the time for describing people from India.

Back then, The Natal Witness and the Natal Mercury published twice weekly and the latter reported on the arrival of the Indians in its edition of November 22. Both the Mercury and The Witness reflected the concerns of the white settler community around the immigrationand much was made of the fear that the immigrants might bring disease with them, particularly cholera.

“Happily on Saturday morning every fear was set at rest,” wrote the Mercury, “by the favourable report of Dr Holland, the health officer, who boarded the Truro at daylight, and found that she was in every respect healthy. There had been neither deaths nor sickness on board.”

However, the Truro had arrived earlier than expected and the depot or barracks where the new arrivals were to be accommodated before travelling to the places where they would work was not yet ready.

“The barracks were not completed. Whoever expected they would be? Was any work, ever executed by any Government, ready for an emergency?” The barracks “would just afford shelter from the elements, and that was all”.

Another problem was that the agent, Edmund Tatham, whose job it was to facilitate the immigrants’ allocation to the white settlers, was away in Pietermaritzburg on business. This was not quite a dereliction of duty as his salary only commenced with the arrival of his charges.

Once the Truro and its passengers had been declared disease-free, it was decided to land them as soon as possible.

In the 1860s, there was no harbour and passengers had to be ferried to the shore from their ship by a smaller boat able to negotiate the offshore sandbar.

Accordingly, on Saturday afternoon, the Pioneer “brought in two large boats for the long-looked-for labourers, leaving about 100 for deportation the next morning”.

The anonymous Mercury reporter provided an eyewitness report of the event: “A very remarkable scene was the landing, and one well worth remembrance and record. Most of the many spectators who were present had been led to expect a lot of dried- up, vapid, and sleepy looking anatomies. They were agreeably disappointed. As the swarthy hordes come pouring out of the boat’s hold, laughing, jabbering, and staring about them with a very well-satisfied expression of self-complacency on their faces, they hardly realised the idea one had formed regarding them and their faculties. They were a queer, comical, foreign-looking, very Oriental-like crowd. The men with their huge muslin turbans, bare scraggy shin bones, and coloured garments; the women with their flashing eyes, long dishevelled pitchy hair, with their half-covered, well-formed figures, and their keen inquisitive glances; the children with their meagre, intelligent, cut and humorous countenances mounted on their bodies of unconscionable fragility were all evidently beings of a different race and kind from any we have yet seen either in Africa or England.

“There has seldom been such a crowd at the Point as there was on Saturday. The boats seemed to disgorge an endless stream of living cargo. Pariahs, Christians (Roman Catholics), Malabars, and Mahometans, successively found their way ashore. The major portion of this lot are, we understand, not so much field labourers, as mechanics, household servants, domestics, gardeners, and tradespeople. There are barbers, carpenters, accountants, and grooms amongst them. Among the women we find ayahs, nurses, and maids. It seems to be rather a heterogeneous assortment, comprising a few of all callings, than a supply of labour for the plantations … They were all provided with two days’ rations from on board, consisting of rice, fish, ghee, and dholl. Each of them carried his household chattels in a teakwood box, and may appear to be flush with spare cash, which they immediately endeavoured to invest in the purchase of ‘something to warm them’.

“After all that had to be landed that day were ashore, the whole body was taken to the barracks, where they have been kept confined ever since. A few men, whether privileged by position or otherwise we know not, have been exempt from surveillance, and have perambulated the town for two or three days past, to the infinite curiosity of a large crowd of Kaffirs, who dog their footsteps, and narrowly scan their movements.”

The Witness’s coverage of the event appeared in its edition of November 23 and was more in the nature of an editorial than a news report. The, again anonymous, writer noted that the paper had been opposed to the introduction of indentured labourers. Initially this was on the basis that there “were no funds for carrying out the project”. Later it raised concerns that “it was a move designed to raise land prices rather than to supply the labour market”, and was critical of money being raised to fund the initiative by implementing an unjust tax on Zulu labourers on “their NECESSARIES of life, such as blankets, and on their agricultural implements”.

The Witness also objected to the fact that the imported labour was intended only “for the inhabitants of the warmer localities on the coast. To this, it may be said, with some force, that any addition to the supply of labour for one part of the community sets free for competition the hands of natives that would otherwise be employed where Coolies will now be engaged.”

But the newspaper’s major objection revolved around the nationality of the imported labourers: “If immigration was desirable, and funds were available to facilitate it, then it was the duty of the colonists to bring to this settlement British hands — hands waiting for work — from our native land, whose flag defends us. Nor was the force of this objection diminished by the consideration of British immigrants being of a class preferentially entitled to the advantages a British colony represents, by the fact of their being morally, socially, and in every sense the best men to be added to our strength.

“Another objection to this system was suggested by the character of the people to be introduced. It may be a question how it is liberal to seek to keep out any race of men; but where a selection is available, it does not appear unreasonable that the intelligent and enterprising of our own language, loyalty, and views of right and wrong be preferred.”

The Witness article ended on a smug, self-congratulatory note: “If, however, the suggestions against the system are ill-founded, no evil will result, and the obligations of the press, to present even unpopular suggestions on public questions, as they arise, will have been discharged. On the other hand, if our fears, especially as to the introduction of desolating diseases, amidst a helpless people, unprepared in any way to guard against the danger … should be realised, then we shall have the satisfaction of having, in due time, and on numerous well-considered grounds, warned of the danger.”

The next day, the Star, having also been opposed to the immigration, accepted that it was now an “accomplished fact” and pledged its support to make the venture a success, concluding that “by securing a constant supply of labour, it will be quite worthwhile to submit to a few minor inconveniences for the sake of securing so great a boon to the colony.”

Source : By Stephen Coan – www.witness.co.za

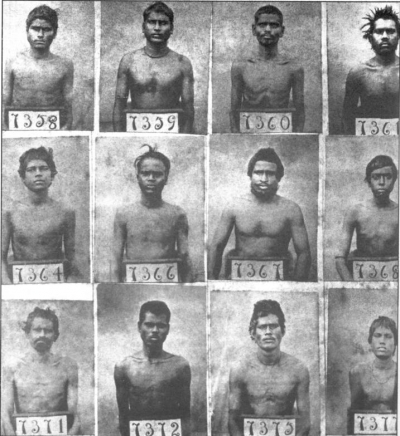

Photo : Inside indenture : Aswin Desai and Goolam Vahed